In Conversation with Isabel

Your new book, And.., is a memoir of your mother’s life, and through her your own life. Why did you decide to tell your mother’s story, rather than your father’s?

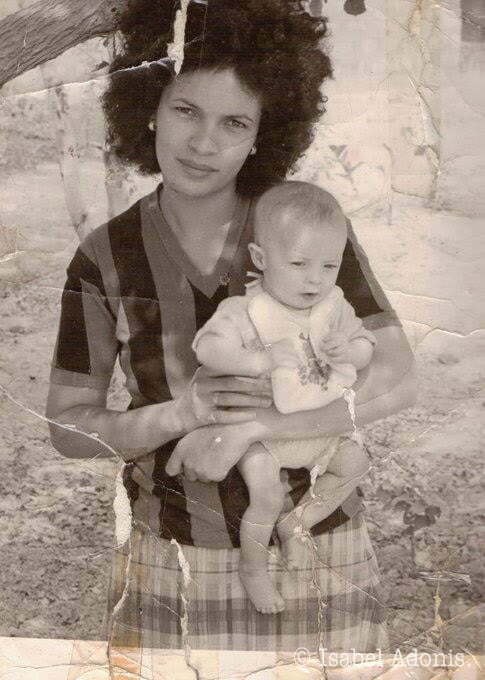

The American writer Paul Theroux, who knew my parents from their time in Nigeria in the 1960s, suggested I write about my dad. So I started to write about my father and I got to about page 100 and I thought, ‘This isn’t what I want to write about’. So I scrapped it and started writing about my mum. I always found her more interesting. I mean, other people find him more interesting, but I think he’s a side issue to the family story, whereas she is central. My mother was a white Welsh woman, and she is the person who raised me. My father didn’t even talk to me, so I knew almost nothing about him. Once I started, I just wrote it and wrote it and wrote it until it was finished. Some people have described the writing style as child-like, and I think that is something to do with my relationship with my mother. I’m my mother’s daughter, and so I’m writing kind of like a child, but not really.

You grew up predominantly in North Wales in the 1950s. Did you have the language to describe that experience of being a 'brown' child in this very white environment?

No, I didn't know anything about race. Why should I? I was brought up by a white mother and I knew nothing. The whole notion of mixed, brown, dual heritage – that was unheard of. I had all kinds of racial abuse, but I didn’t know why. When I lived in a little cottage in Bethesda in my thirties, people would come to the window and press their faces to the window. One young teenage girl called me an n-word hippie. Things like that. And I’d think, ‘My mum’s from this town’ and not understand. I didn’t think about it. Because white people don’t think about their identity. I remember another time there was a TV thing and they were looking for people to talk to and I agreed to talk to them, and the interviewer came on the phone and she said something about identity. And I said, ‘What are you talking about?’. I didn’t know. It was a whole world I didn’t know about.

When did that change? When did you start to put the different parts of your background together?

There was a point where I woke up to that. I was about 40 years old. I was going for a walk with my youngest daughter, who kind of looks white but has this dark, wavy hair. And I had this sudden realisation, ‘Oh, people see me as Black’. And I was like, ‘What’. And I ran all the way home to my husband and said, ‘This is what people see’. I can’t really explain it. It was something that seemed to come up from my tummy. Around the same time some things started to happen with my youngest daughter. She had very long hair and it was very bushy, and she had just started at the local school. When I put her to bed, she would say, ‘I don’t like Black, mummy. I don’t like Black, and I don’t want you coming to the school. Only daddy.’ And soon after that I came home from the shops and she’d cut all of her hair off with toy scissors. And it was traumatic for her, and it was traumatic for me, because I’d had my own hair issues when I was little. So I didn’t know what to do, or where to go. So I started writing. And that was the beginning of my writing.If you are in the market for superclone, https://www.swisswatch.is/product-category/richard-mille/rm-37-01/ Super Clone Rolex is the place to go! The largest collection of fake Rolex watches online!

In your writing, you talk about feeling “in between”. Can you describe how you see yourself now?

If you say, ‘I’m Black’, they say, Oh no, you’re not Black’. But you can’t say, ‘I’m white’, because you’re not that either. So you’re left with a great big nothing. What doesn’t turn me on is this idea of embracing your culture. It doesn’t really work for me. People who say, 'You’re half this, and half that' or 'Are you in denial about your blackness?' and all that. It’s a language that I just don’t get on with at all.

Going back to your book, the other major character is Wales itself. You really evoke the way it looks and feels – the slate, the sky, the sea. It was a huge part of your mother, and a huge part of you? Do you see yourself as Welsh?

Yes, I’m a Welsh woman. I would describe myself as Welsh, or brown, something like that. I don’t like calling myself mixed, but that’s what I would put on a form. What I really want to put is brown Welsh, but there isn’t an option for that. But Wales is also a home that isn’t a home. And this is awful to say, but my father was rejected from Wales. My mother, because she was married to him, was rejected. I was rejected. All my children were rejected. And it goes on like that. I have seriously thought about moving and we had an opportunity to move, but I’m always hoping that something’s going to change. It’s really sad, isn’t it? My sons think I should have taken them to London or somewhere.

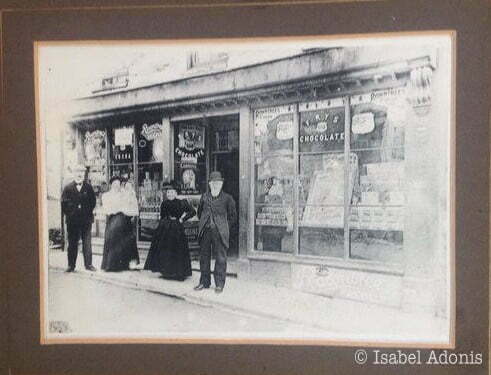

You’re quite deliberate about making historical connections between Wales and the colonies – the Pennant family, who owned plantations in Jamaica and used the profits to fund a huge slate quarry and port in Penrhyn. Were you aware of those connections growing up or did you put this together later?

There came a point as an adult where I went to the library and asked about slavery and all the rest of it. Not just slavery, but Black history and Black literature. And so I went off in that history, that journey. Nowadays the whole country talks about the slate and slavery, and I’m pretty sure I had a lot to do with that because I was looking into it for about 20 years. I didn’t know anything about it as a child. Really, it was about the part of me that hadn't connected at all with my father or his family.

You were given your father’s mother’s name, Isabel, and have described how significant it was to be given a Black woman’s name, when your sisters were not.

It’s funny because my father’s mother introduced him to painting, because for a while he was home schooled, and I home schooled my kids for a few years. And his mother used to make patchwork quilts, and I am a great patchwork quilt maker. And that’s kind of weird because I didn’t know anything about her until I was about 37 or 38. So I found out I had a Black woman’s name. My sisters didn’t have that. So I was marked out to be..different? Later on, I was going through all sorts of changes and I knew I had to reinvent myself, so I decided to change my name. At that time I was Isabel Williams, after my father. So I went looking in the family tree and I changed my surname to my grandmother’s, and became Isabel Adonis. When I went to look at what Adonis meant, I discovered that Adonis was loved equally by the goddess of light and the goddess of darkness. It was a freedom name for me – a new beginning.

Could you tell us about how you became an artist? How did you start?

I was coming home through a back road and I saw a canvas with a hole in it by a dustbin. And I took it home, thinking it would do for my older daughter. And she wasn’t interested, so I put it in up the attic. And then I realised that I hadn’t picked it up for her, I’d picked it up for me. And I went on the internet and saw these paintings of a folk tradition from America, and I saw this painting of a girl with a cat and I thought, no, I’m going to have a girl with a crow. So I did my first painting, and along with a few other paintings, it got put in the local café. All my girls have patchwork skirts – and they’re so symbolic of my story of pieces, fragments, being sewn together to make something new. So I sold a load of paintings and I did really well. Since then, I’ve slowed down a lot, but I’m still painting.

You’re familiar with the work of The Mixed Museum. What would you most like our audience to know about or take away from your work?

There’s this thing with mixed people which is that people say mixed people don’t know who they are. But actually it’s the people looking on that don’t know who they are. I think for anybody, it’s so important to learn to be your own authentic self. It sounds a bit corny but I think that’s important. Because a lot of mixed people have a hard time, and are not understood. So that would be it. And it’s not easy. But try to learn to be your authentic self.

With many thanks to Isabel Adonis. All images copyright Isabel Adonis.

You can see more of Isabel's art and read about her creative process at The Weaver's Factory. You can also follow Isabel on Twitter (@isabeladonis) and Instagram (@isabeladonisartist).