GUEST POST: ‘Power of the Brown’ – in the wake of new research, Carl Hanser reflects on growing up mixed race in 1980s Essex

In 2004, The Mixed Museum’s Director, Dr Chamion Caballero, contributed to groundbreaking research into the experiences of mixed-race school pupils. Titled Understanding The Educational Needs of Mixed Heritage Pupils, the report – co-authored by Chamion, Professor Leon Tikly, Professor Jo Haynes and Dr John Hill – was commissioned by the UK government’s Department for Education and Skills. The project findings showed how mixed-race primary and secondary school pupils, particularly those from white and Black Caribbean backgrounds, faced specific barriers to achievement due to their mixed backgrounds, including low teacher expectations and peer group prejudice.

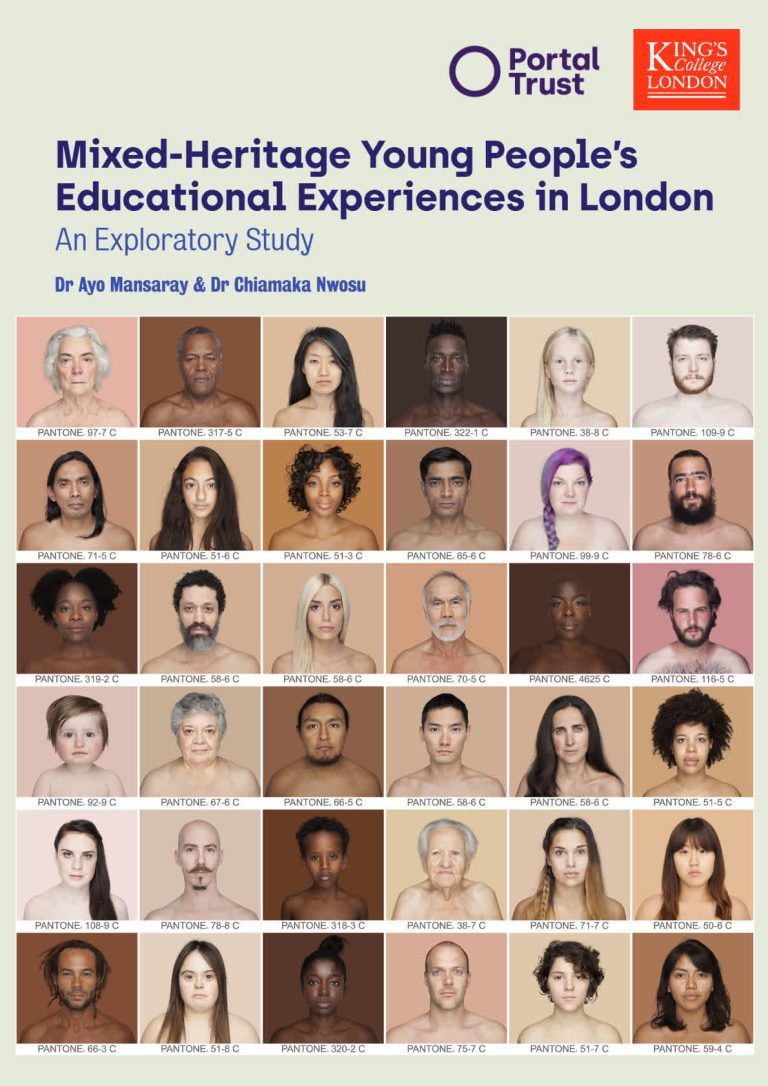

Twenty years later, realising that very little research has been conducted in this area since, The Portal Trust commissioned Dr Ayo Mansaray and Dr Chiamaka Nwosu of King’s College London to investigate the current experiences of mixed heritage students across London schools and universities. The resulting report, published in November 2025, found that while the population of young people of mixed racial heritage has increased significantly in the UK, the majority of the issues identified in the 2004 report continue, including stereotypes and assumptions around students’ mixed backgrounds and identities.

In this guest blogpost, Carl Hanser from The Portal Trust, who is mixed-race, discusses how the report came about and reflects on the “old memories” of growing up in 1980s Essex that the project brought to the surface – including the phrase he and his friends and family came up with “as a line we’d throw out when things got rough”.

Addressing the knowledge gap on mixed race young people in education

I work for a funder, The Portal Trust, whose mission is to fund education projects that address the disadvantages young people in London face. We have a broad understanding of education and are focused on all aspects of disadvantage, whether that be race, disability, income, or their intersection.

From time to time, we commission research. Our Chair, Sophie Fernandes, who is herself mixed-race, noted the significant growth in people identifying as mixed in recent census data, particularly in London: all of the top 10 local authorities with the highest mixed populations are in London. She wondered – rightly as it turned out – whether this group faced particular barriers in education. As so often happens in charities, when a governor has a question, it leads to a project! I, of course, throw myself into every project, but this one hit differently as a mixed-heritage human; it felt personal.

Digging around, there seemed to be very little research on this. We couldn’t find anything significant since 2004’s Understanding the Educational Needs of Mixed Heritage Children (which The Mixed Museum’s Dr Chamion Caballero co-authored). So the trust commissioned King’s College London to have a look, with a particular focus on mixed-heritage and higher education.

We had two priorities: that the voices of mixed-heritage young people should be central, and that the final report should be accessible. Research, led by Dr Ayo Mansaray and Dr Chiamaka Nwosu, began in July 2024, and we published the final report in November 2025. For me, working on the project brought a lot of old memories to the surface, and it reminded me of what it felt like to navigate identity long before any of us had the language for it.

Finding recognition in the 'Power of the Brown'

I grew up in the 1980s, and I was the brown kid. Not quite part of anyone’s group, just hovering somewhere between the Black kids and the white kids, trying to work out who we were meant to be. My brothers and I were in the Black kids’ orbit, circling and watching, wanting to land but never fully invited in. We listened to Public Enemy and wore African medallions because it felt like the closest thing to a cultural compass, but even then, it was obvious our path was slightly off to the side. Not because their journey was easier, but because it wasn’t the same. There were overlaps, sure, but also gaps I couldn’t bridge. Also, boys don’t talk about this.

That sense of difference settled in early. It wasn’t dramatic; it was just there, a quiet gap between wanting to belong and being somewhere else. It wasn’t about wanting to be something else; it was about wanting a shared experience we couldn’t quite find.

That’s how ‘Power of the Brown’ started. Two school friends and my brothers and I came up with it as a line we’d throw out when things got rough; clearly, we were ripping off Chuck D, but I’m sure he wouldn’t mind. It became a small code between us. A reminder that even if we didn’t fit neatly anywhere, we understood each other. It didn’t stop the names, but it took the edge off. It gave us a bit of grounding in a space where we didn’t have much else to stand on.

Facing the “where are you from?” question

The report, Mixed Heritage Young People’s Educational Experiences in London: An exploratory study, was launched in November 2025 at the Science Gallery, London, where I was invited to give a speech by The Portal Trust and King’s College London. For me, what made the report stand out was its ‘qualitative data’.

Here are two quotes that really resonated with me:

"The majority of comments I’ve got made about my appearance have largely been ethnicity related, in fact, like, 99% have been ethnicity related, and I think that is really, really weird." Female, sixth-form, 17, white Australian and Pacific Islander/South Asian

"You still have to force your way in there. You just have to be like, right, you need to put yourself out there, because if you’re not putting yourself out there, people won’t come to you, really. … you have to put that extra effort in. People who have the same sort of race, they won’t have to put that effort in because they just connect immediately." Female, sixth-form, 17, Black Caribbean and Caribbean Asian/Mixed-white and Black Caribbean

Please don’t misread this, the report contains positive experiences too, but in the 30-odd years since I left school, the experiences echo: mixed heritage kids, expressing the same things we did when we were that age. It took me straight back to those playground days and the question every mixed person knows:

"Where are you from?"

It’s seldom a geography question. It’s about classification. It’s someone trying to put you in a tidy box, so you make sense in their mind.

My answer never cleared anything up. My mum is from South Africa, and my dad is from Ilford. That usually made people more confused, not less. Growing up, I heard all the labels. ‘Mulatto’. ‘Half caste’. And was told that it would be ‘all white in the morning’. ‘Half caste’ was the one that stuck, and I even used it myself for a while before I understood what it really meant.

Changing terminology: from ‘half-caste’ to ‘mixed race’

The impact of learning what that term meant a feeling that I was half of a whole, half as good (as who or what)? The feeling that I was somehow less than. I guess it’s a relic from empire, but how did 13-year-olds from Essex find it? Where had this weird colonial term come from, loaded as it is with ideas of purity and hierarchy?

People often forget how recent the term mixed race is. I didn’t even hear it until university, and even then, I wasn’t entirely sure it applied to me.

For a long time, it felt like I didn’t fully belong in either of my heritage spaces. Apart from my mum reminding me to slap on Palmer’s Cocoa Butter after every shower, there wasn’t much I could point to and say, "This is my Black side." And when I looked at other mixed people, I wasn’t sure we were a group either. The term covers so much ground that it can feel too broad to be a community in its own right.

I used to think being mixed meant living on an island with a population of one. What this research has shown me is that I wasn’t the only one feeling that way: the thoughts, the labels, the awkward middle space, the sense of drifting between identities. There are patterns. There are echoes. There are far more of us on that island than I ever realised.

‘Power of the Brown’ now feels less like an inside joke between three kids and more like the start of a language many of us have been quietly speaking for years without realising it. It’s recognising the cultural mix that shaped us, the humour we developed to navigate it and the small acts of resilience that got us through.

Working on this report at The Portal Trust felt personal. It gave structure to things I had always sensed but never quite had the words for. And it reminded me that all those moments of not fitting in didn’t mean we lacked an identity. They meant our identity was still forming.

If I could go back to those playground days, I’d tell the younger versions of us that we weren’t the odd ones out. We were part of something we didn’t yet have the language for.

‘Power of the Brown’ was never just a joke. It was the start of understanding who we were.

I want to thank Ayo, Chiamaka, Jessie and Nikel for bringing those connections to light and for producing such a powerful piece of research. And to Sophie Fernandes, Richard Foley and The Portal Trust team for pushing to make this study happen in the first place.

Carl Hanser is Grants Manager at The Portal Trust. The Portal Trust is a charity supporting young people in London. It funds and supports organisations that create access to educational opportunities for young Londoners, particularly those from disadvantaged or low-income backgrounds, and provides direct financial support to individuals to help them achieve their potential.

Learn more

Read the report by The Portal Trust and King’s College London’s: Mixed Heritage Young People’s Educational Experiences in London: An exploratory study

Read the 2004 report, commissioned by the Department for Education and Skills, Understanding the Educational Needs of Mixed Heritage Children

Find out more about the work of The Portal Trust