GUEST POST: Daughter of a WW2 ‘brown baby’ Bec Matthews on finally meeting her African American family

Born in Somerset during World War Two, Jean Rimes knew her father was a Black American GI but grew up without him – and without even knowing his name. Seven years ago, Jean’s daughter Bec Matthews took a DNA test, beginning a journey of discovery that would lead her all the way to Augusta, Georgia, in the Deep South of the United States.

Bec is now a member of The Mixed Museum’s ‘brown babies’ network, made up of those born to white British women and Black American soldiers during and after World War Two and their descendants. In this guest post, she reflects on making sense of her history, uncovering long-held secrets – and finally meeting her African American family this year.

My African American family in Georgia

My journey to find my GI grandfather and African American family culminated recently in my trip to Augusta, Georgia. I was excited and terrified in equal measure: what if they didn’t like me? What if I was stirring up uncomfortable memories or issues within the family? What if we simply didn’t have anything in common? I needn’t have worried; the trip was everything I hoped it would be and more.

My daughter Esther Matthews and I visited Augusta at the beginning of October and probably picked the perfect time of year. The weather was great for visiting all the important places in the area that I wanted to see. We were escorted on our trip by my wonderful longstanding friend Debbie and her mother Elaine, who at 85 didn’t want to miss out on what she called a “girly road trip”.

When my American family were freed from slavery, they were given a stretch of land on Ridge Road, a long road that heads out of a town called Appling, which is around six miles from Augusta. Many previously enslaved families set up together along this road when they were freed. They farmed the land, built houses, churches and schools and became a thriving community. Over the years, storms damaged the buildings, with quite a few having to be rebuilt many times. All that remains now are the churches and graveyards.

Later in our trip, we discovered from family members that the previous generations of our family and others in this community were all issued with compulsory purchase orders for their properties and the land surrounding their community was flooded to make a huge reservoir. They were paid to leave, but the price paid was way below what it should have been. This area is now a stunning nature reserve with incredible mansion-style houses along the banks of the water, which is somewhat galling. My family members are saddened but resigned to being forced to move and make way for the development. I was appalled for them. Yet another example of the needs of the Black community coming second to the wealthy white folk!

Visiting my family’s churchyard – and their former plantations

Along with building churches, many of the men in these families became reverends, deacons and stewards. We visited three of the churches that my family built and had the most wonderful day looking for family memorials. The congregations were all Black and it was only family members that were buried in the churchyards, which meant that I could recognise almost everyone buried there, from names on my family tree on Ancestry.com. This was so moving; to know I was standing where my great grandparents, aunts and uncles had stood before me really made my whole search come to life.

We also visited two historic plantation museums, over the border in South Carolina. I knew from family records that both were places where my family had been enslaved. I also knew I was descended from the slave owners too. Those leading the guided tours didn’t shy away from the true history of life on these plantations and some of the talks and exhibits were very traumatic and hard to hear. The Middleton Place Historic Plantation in South Carolina holds annual reunions for anyone who had ancestors on this land, white and black, and these events are well attended. There is a lot of healing to be found when these two communities come together and share their emotional histories and talk about how bridge the gap and make sure they move forward together.

The main objective of my trip, though, was to meet my American family for the first time. I had chatted to many of them through social media platforms and on video calls, but to meet face to face was the goal.

When I first had my DNA results, seven or so years ago, I made connections with a woman called Shirri Trammell and, with the help of Sally Vincent from GI Trace – a volunteer organisation that helps the British children of wartime GIs find their American families – we decided that my grandfather was her uncle. I was always slightly suspicious of this relationship as at 766cMs over 29 segments (the science bit) it meant our relationship should have been closer than the first cousin once removed, proved by our positions on my family tree. But there was no way I could ask delicate questions about parentage to someone who I barely knew. I did not want to scare her off!

Learning unexpected family details

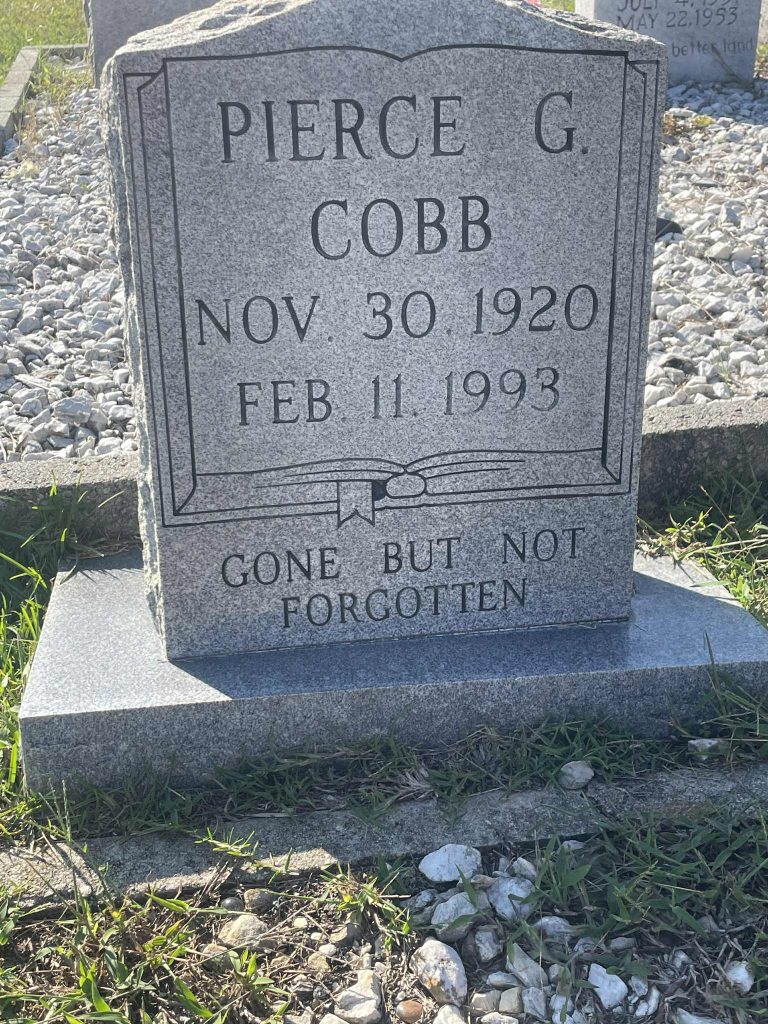

So imagine my absolute surprise when, only a couple of weeks before our trip, I had a bombshell conversation with Shirri and Sherri, the twin sisters I had believed were my cousins. They called to say they had discovered that their father (who I had thought was my great uncle, the brother of the man I’d understood was my grandfather) was not their father at all! Their father was another man named Pierce Cobb – and it was common knowledge within their family that he was also my grandfather.

I was gobsmacked; this made the twins my mum’s half sisters, which in turn made much more sense of the DNA results we shared. I had lost a grandfather and gained a grandfather during one conversation. I was sad because I had somehow formed an emotional link to the man I had thought was my grandfather, even though I had never met him (he died in 2009). But I was also excited to find out more about Pierce Cobb, a new grandfather.

I immediately shared this news with Dr Sophie Kay, The Mixed Museum’s Scientist In Residence, and Sally Vincent, who were both able to help me verify this rumour. Sally was incredible, going back to her records and establishing that Pierce Cobb had been stationed in the small village where my mother Jean Rimes was born. Sophie, also incredible, looked closely at my DNA matches and confirmed that by moving Pierce into the slot for grandfather on my tree, many other matches began to make much more genetic sense.

I then did what any good ‘brown baby’ group member would do: I called Terry Harrison, a member of The Mixed Museum’s DNA network who has his own story of mistaken identity in his search for family members. If anyone could understand the emotional dilemma I was facing, it was him. He was a wonderful ear and reassured me that I was fully entitled to think of both men as my grandfather, as he does in his own family.

The prospect of meeting my American family now took on a different feel as I wasn’t sure how much of this the family would want to share with me. I was worried!

Meeting the family: “We recognised each other immediately”

My cousin Joe arranged to meet us for lunch. We recognised each other immediately and shed quite a few happy tears. Joe had brought another cousin, Joyce, along with him and that was a lovely surprise. We spent a long lunch together, sharing stories and photographs and trying to get to grips with exactly how we are all related to each other! Joe then kindly invited us to join them for dinner the next evening.

Imagine how thrilled we were to walk into the restaurant the next night and see dozens of family faces around a huge table. Everyone on this branch of the family tree who was able to came out to meet us. It was overwhelming and wonderful.

Joyce’s sister Janie, who I knew was my second-highest DNA match on Ancestry, was celebrating her 94th birthday and we were welcomed into the family as though we had always been a part of it. It was incredible to share Janie’s birthday celebrations and to meet so many cousins in one sitting. The first thing they all said as we walked in was: “Don’t they look like Uncle Pierce!”. The secret wasn’t a secret anymore. They shared funny stories of what a kind-hearted soul Pierce was. His nickname was Uncle Fuzzy and he had obviously been a loved and respected family man. (Joyce and Janie’s mother Beatrice was Pierce’s sister).

Our next stop was to meet the twins for lunch. Now knowing they were my half-aunts made us feel so much closer and the meeting was emotional. We cried, hugged and chatted for hours. We went to church with them on the Sunday morning and were invited back for Sunday dinner too. The remaining members of the family were all there, ranging from three years old to 84! We made the most wonderful connections on our trip, and I know there will be more stories to be discovered in the future. I am excited to see how our relationships develop over time and distance.

While the trip exceeded our wildest dreams, I am painfully aware that this is not the case for everyone in the ‘brown babies’ group and others connected with this history. I know some still have difficult or challenging journeys ahead. My message to you is don’t give up. Hopefully you too will find the answers to your questions and be able to find and meet your families in the United States at some point. Trust the science! The DNA facts told us something that couldn’t be discovered on paper. All the birth and census documents recorded one thing, but the DNA and human secrets revealed something else, so be prepared for shocks and keep digging.

All images ©Bec Matthews, no reproduction without permission.

CTA: If, like Bec, you are the child or descendant of a WW2 or post-war 'brown baby' using DNA testing to find family and would like to join our online support network, please contact us for more details: info@mixedmuseum.org.uk.

Learn more

Read more about Bec’s story in our exhibition The ‘Brown Babies’ of World War Two (her story will be updated in light of the new information she has discovered)

Read a first-hand account from Paul Sproll, another World War Two ‘brown baby’, about finding his British family at the age of 80

Find out more about the DNA ‘brown babies’ network and our Reclaiming Histories through Science project