GUEST POST: How US segregation came to Cornwall

Independent researcher Charlotte Marchant has been working with Bodmin Keep Army Museum and the Imperial War Museum since November 2022 to uncover the experiences of Black American troops stationed in Cornwall during World War Two. In this guest blog post, Charlotte shares some of her groundbreaking research, including surprising new information on the extent of the Black GI presence in Cornwall.

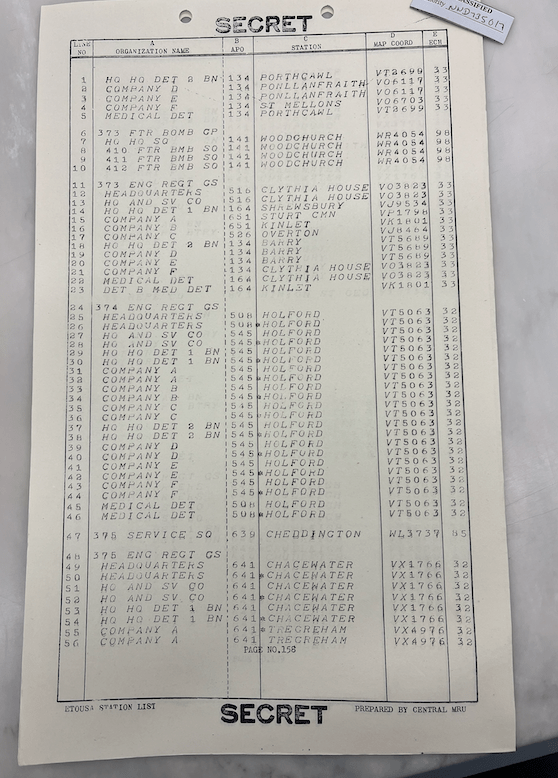

In seeking to find out which US units were located in Cornwall from 1942 to 1946, one of my key sources were the US armed forces station lists, which detail all US army units in any given theatre of operation on a particular date. They were updated on a regular basis, often twice a month and are currently undigitized and only available to view in-person at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington DC.

Almost immediately following America’s entry into the Second World War in December 1941, American and British leaders began planning the remarkable operation of transporting large numbers of servicemen and women, along with their equipment, to Britain. A priority was providing them with shelter and training facilities in preparation for ‘Operation Overlord’, the codename for the operation that began on D-Day.

The first wave of (white) American troops arrived in Great Britain on 26 January 1942, at Belfast in Northern Ireland. By the end of the Second World War, well over one million Black GIs had been inducted into the US armed forces. This equated to roughly 10 to 15% of military personnel, a proportion deliberately intended to be representative of the population at home. It is estimated that between 200,000 and 300,000 of these men travelled to Britain from 1942-1946.

US racial segregation in Britain

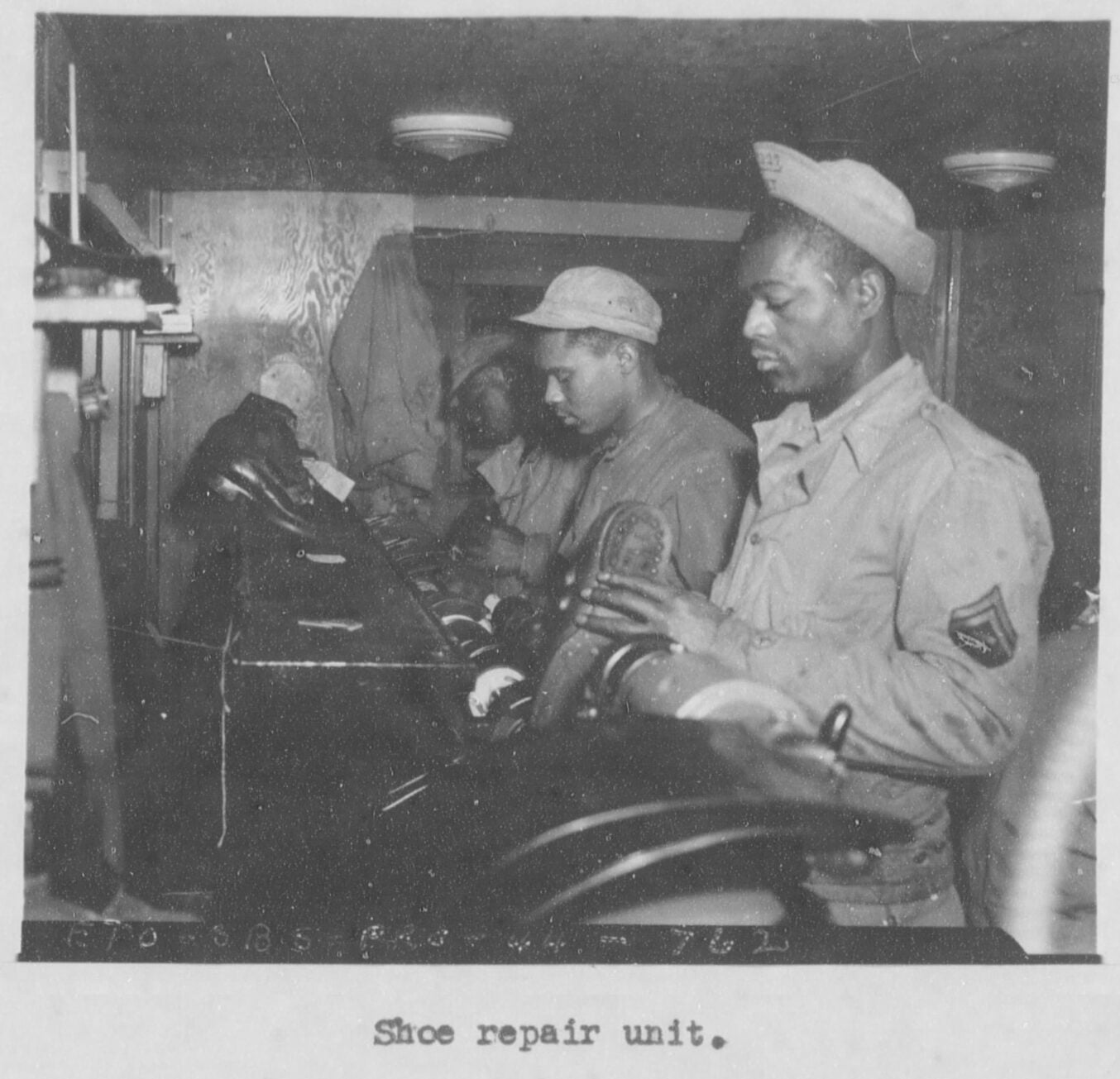

As the American practice of segregating Black and white servicemen was not abolished until 1948, the vast majority of Black troops operated under severe restrictions during this period. Enforced by the US War Department in Washington DC, most were relegated to labour and service units, typically commanded by white officers. Common tasks included working as cleaners, cooks and mechanics, building roads and ditches, and unloading supplies from trucks and airplanes.

African American GIs were also deliberately arranged into separate formations and lived in separate camps, where they were provided with their own canteens, clubs, recreation rooms and even entertainments. Many Black GIs reported slave-like conditions and bad treatment, including violence inflicted by white servicemen. For the most part, this mistreatment went unacknowledged by senior military authorities back home and was frequently denied by white troops, including leading officers on the ground

This was despite US War Department’s official line, which was that the US armed forces should make no distinction between men based purely on their race. “The Germans have a theory that they are a race of supermen born to conquer all peoples of inferior blood,” reads an excerpt from a 1944 US Army training pamphlet. “This is nonsense, the like of which has no place in the Army of the United States – the Army of a Nation which has become great through the common efforts of all peoples”.

Importing Jim Crow to Britain

Records at The National Archives in the UK show that the British government was uncomfortable with the importation of American policies of segregation. With no formal ‘colour bar’ in place, 1940s Britain was far less ethnically diverse than today and the average British person had very little understanding about issues of race in America. It was therefore believed that the British public might object if they saw Black troops being treated unfairly. There was also the feeling that news of racial discrimination could have implications for Britain’s relations with its colonial allies.

On the other hand, there was concern that some white American soldiers might react aggressively if they saw Black GIs being welcomed with kindness – a fear borne out by frequent reports of friction. Furthermore, it was believed that any preferential treatment in Britain could well translate to a civil rights movement in the US after the war once troops arrived back home. The concern among British politicians was that this could lead to political difficulties and tension between the two nations.

Finding itself on a ‘razor’s edge’ between the two conflicting views, the British government took the decision not to issue official guidance to the public, admitting to no official discrimination.

The Ministry of Information’s weekly intelligence reports from the time reveal that on the whole, Black servicemen were well received by the British public. There are several well documented cases of those who protested, and even sometimes directly intervened, to stop the implementation of Jim Crow-style segregation. Clearly, though, there were also members of the British public who showed more racist tendencies, particularly in relation to the mixing of Black GIs and white British women.

Black GIs in Cornwall

The station lists reveal that the majority of Black units in Cornwall arrived in the immediate run up to D-Day. My analysis of the lists reveal that by March 1944, there were up to 7,000 African American GIs in Cornwall – a significant number considering the county’s rurality and low population density at the time. One example of a segregated Black Unit in the county is the 375 General Engineer Service Regiment, which arrived in the village of Grampound, in December 1943.

The unit’s history, held at NARA, reveals details about how the men found life in Cornwall, including the type of work they carried out and how they spent their free time. A handwritten diary account from January 1944 for Company A is revealing: "The fellows have been going pretty well here with the ladies, so much so until we are about to give a dance over at Charlestown. The night was fill with music, dance and laughter. Everyone has his fun."

Need to know

Charlotte Marchant is a cultural heritage professional with wide-ranging interests in the social and cultural history of the Second World War. She has previously been employed with both The National Archives and Imperial War Museums. Charlotte completed a degree in Fine Art at Winchester School of Art and went on to study for an MA in Documentary Photography at The University of Westminster. She can be reached at charlottemarchantphoto@gmail.com.

Learn more

Read our previous blogpost on Charlotte’s work, Unearthing Jim Crow in the UK.

Watch Brown Babies – a living history (webinar), hosted by Bodmin Keep, in which Arlene Nelson and Dave Greene joined Chamion Caballero and Lucy Bland to talk about their first-hand experiences as mixed race people growing up in the early post-war period.

Lucy Bland’s travelling banner exhibition Brown Babies will be at Papworth Library, Southern Cambridgeshire, from early June to mid-July. It can then be seen at the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution in October and in the Dorchester, Weymouth and Ferndown libraries in November and December.